Starts October 28

Benjamin Espòsitos (Ricardo Darin) is a retired policeman and he cannot forget an especially brutal rape / murder of a young woman that happened 25 years ago. He decides to write a novel on the topic and, for research, he contacts Irene Hastings (Solead Villamil) who was his boss and also the judge on the case. At first, police suspected the young husband Ricardo Morales (Pablo Rago); then they arrested two constructions workers, mostly in order to close the case quickly, not because of any overwhelming proof. In the end Espòsitos and his Sancho-Panza-type sidekick Pablo arrest the real murderer: a former boyfriend of the victim. Soon the murderer is free and working for the government.

Benjamin Espòsitos (Ricardo Darin) is a retired policeman and he cannot forget an especially brutal rape / murder of a young woman that happened 25 years ago. He decides to write a novel on the topic and, for research, he contacts Irene Hastings (Solead Villamil) who was his boss and also the judge on the case. At first, police suspected the young husband Ricardo Morales (Pablo Rago); then they arrested two constructions workers, mostly in order to close the case quickly, not because of any overwhelming proof. In the end Espòsitos and his Sancho-Panza-type sidekick Pablo arrest the real murderer: a former boyfriend of the victim. Soon the murderer is free and working for the government.

At first glance director Juan José Campanella has made a classic detective story with two tragic love stories: one between two young people of whom one dies, the other the unfulfilled, endless love of a middle-aged policeman for his boss who is married. Politics are involved in that the film occurs in 1974 during the military dictatorship in Argentina. This provides a background, and perhaps an explanation why a convicted murderer is released from prison and allowed to work undercover for the government, but it is not a political film. And its not really a classic detective story. There are many nuances concerning memory, loyalty, brotherly love, and revenge. As the press notes correctly say, “By going over his memories a thousand times, Espósitos suddenly sees the past with different eyes, and that, in turn, changes his future.”

Campanella said that in his mind’s eye he saw an old man eating alone and he wondered why. What would that man say? He is interested in the theme of enduring undeclared love. He wants to know if there are secrets that show up in our eyes, which we could decipher if we would stop and look. Do our eyes really give us away?

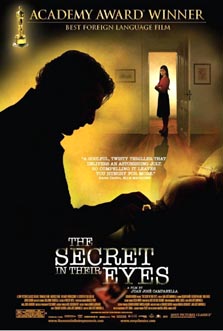

This is an excellent film, not only because it won the 2010 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, against strong competition: The White Ribbon, Ajami, The Milk of Sorrow, and A Prophet. Here, nothing is obvious at the beginning. Half way through you think the film is over. Then there is a surprise ending. I would love to watch it more than once, in order to appreciate the excellent camera work by Félix Monti as well as the music by Federico Jusid. It’s amazing how the opening of a gate can be made crucial just by using a certain camera shot. My favourite scene was in a soccer stadium with thousands of people. I thought it was symbolic of the whole film: we are blind until we “see” the essence.