Starts October 20

Original language: Spanish

Who doesn’t wait with bated breath for the newest Almodóvar? This one will leave you with breath still bated as you walk out of the cinema, while scratching your head.

Who doesn’t wait with bated breath for the newest Almodóvar? This one will leave you with breath still bated as you walk out of the cinema, while scratching your head.

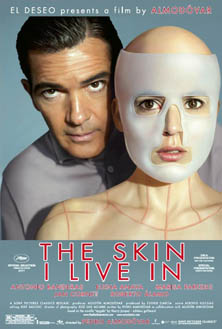

Antonio Banderas (who got his start with Almodóvar with Labyrinth of Passion in 1982 and has been in at least five more of his films since then) has returned to his former director after 21 years to play Dr. Robert Ledgard, a plastic surgeon in Spain. He lives in El Cigarral, a huge villa outside of Toledo with his mother Marilia (Marisa Paredes – also a regular Almodóvar actress since 1984). His mother is also his housekeeper. Ledgard is her successful son, but she also has a second son, Zeca, a gangster, who cut off contact long ago.

Otherwise, the big house is empty, except for a hidden room, painted in grey and controlled by several in-house cameras with TV screens in the kitchen and elsewhere. In this high-security, secret room lives Vera. She is a beautiful woman who does yoga, writes notes on the walls, and receives Dr. Ledgard when he has the inclination or wishes to examine her. Vera is not only a prisoner in the house, but also a prisoner in her skin which is not originally her own. Six years earlier, Vera was a young man named Vincent, whom Dr. Ledgard captured for his great experiment: how to make perfect skin. His interest derived from an event 12 years prior: his wife Gal had been in a terrible accident which left her scared beyond recognition. There was no such perfect skin available then and she suffered to the point that she took her own life by jumping out of the window.

The sets and dialog, as well as movement and speech, are minimal. There is nothing superfluous to distract from the cold-blooded revenge of Dr. Ledgard, who hasn’t the necessary gene to realize that he is making other people suffer. In this atmosphere the music by Alberto Iglesias (who also just wrote for Polanski’s newest film Carnage) is especially effective. There are layers of psychological inferences and subtle references, so that you might want to watch the film twice. Think about not only living within the skin of someone else, but being turned from a male to a female in the process, i.e., losing your identity in two ways. Think about losing your physical, as well as mental freedom, locked in a house as well as in a foreign skin. One scene shows Vincent/Vera visiting his mother’s boutique. She doesn’t recognize him; logically he is expected to try on women’s clothes – with which he cannot identify.

Almodóvar says that he was inspired by Hitchcock’s film Vertigo as well as Frankenstein. French fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier advised about the fashions.

No Almodóvar film is easy; there is always something under the surface, foreign to daily life. Sometimes we can identify with Almodóvar’s situations, but often not. At first glance this story seems far fetched from anything we might experience ourselves. But think about it: it begs for discussions about the disappearance of young people who are never found, our addiction to plastic surgeons and their responsibility, our relaxed acceptance of camera surveillance in our daily lives, and the difference between man and beast – or not. These are definitely topics which we must relate to. Almodóvar fans will be satisfied; others might have to “think” about it – something we all must do more often.