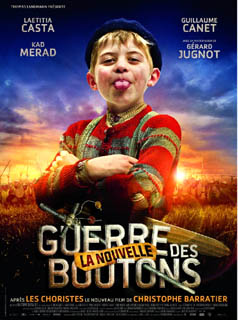

Starts April 12

Original language: French

It’s 1944 in Longeverne, a small farming village in France. Boys of all ages meet in a classroom. They wear knee socks and short pants with suspenders, and heavy leather shoes (no fancy Nikes). They carry old-fashioned satchels full of school books. The families live simply in small houses with a latrine in the back; often there is no running water or electricity. The children are expected to help at home and fathers are hard disciplinarians. Still the boys find plenty of opportunity for activity. In fact, they are highly organized in a boy gang under the leadership of the oldest boy, Lebrac. He isn’t the smartest boy at school, but excellent in planning attacks against the boys of the opposite village of Velrans. Those wretches called them Schlappschwänze or Weicheier. If you can imagine what that means, then you’ll know why harsh retaliation is called for. They stealthily discuss schemes for counterattack and hide in the bushes for greater surprise assaults. When they capture a prisoner, a boy of their own age, he is humiliated and relieved of all the buttons on his jacket and pants. His suspenders are cut and he must run away with his pants around his ankles. This is worse than it seems, because a boy who arrives home without all his buttons will be scolded by his long-suffering mother who must sew on new ones that aren’t cheap. The boys from Longeverne are so victorious that they decide to build a club house to display their huge collection of captured buttons and other war memorabilia. One girl is allowed into the club house and she makes herself useful, sewing on buttons that the victors also lost in battle in desperate attempts to protect themselves (until they agree to fight naked).

It’s 1944 in Longeverne, a small farming village in France. Boys of all ages meet in a classroom. They wear knee socks and short pants with suspenders, and heavy leather shoes (no fancy Nikes). They carry old-fashioned satchels full of school books. The families live simply in small houses with a latrine in the back; often there is no running water or electricity. The children are expected to help at home and fathers are hard disciplinarians. Still the boys find plenty of opportunity for activity. In fact, they are highly organized in a boy gang under the leadership of the oldest boy, Lebrac. He isn’t the smartest boy at school, but excellent in planning attacks against the boys of the opposite village of Velrans. Those wretches called them Schlappschwänze or Weicheier. If you can imagine what that means, then you’ll know why harsh retaliation is called for. They stealthily discuss schemes for counterattack and hide in the bushes for greater surprise assaults. When they capture a prisoner, a boy of their own age, he is humiliated and relieved of all the buttons on his jacket and pants. His suspenders are cut and he must run away with his pants around his ankles. This is worse than it seems, because a boy who arrives home without all his buttons will be scolded by his long-suffering mother who must sew on new ones that aren’t cheap. The boys from Longeverne are so victorious that they decide to build a club house to display their huge collection of captured buttons and other war memorabilia. One girl is allowed into the club house and she makes herself useful, sewing on buttons that the victors also lost in battle in desperate attempts to protect themselves (until they agree to fight naked).

This story is based on the original French book La guerre des boutons by Louis Pergaud. Pergaud said this “reflects my life at age 12.” He was the son of a village teacher and later as a young man also taught in a French village. His book was a big success when it was published in 1912. Shortly afterwards Pergaud entered World War I as a French soldier and fell in 1915, at age 33.

This is the fifth filmed version since 1936. I had the privilege to see the 1962 version directed by Yves Robert, in French, as well as this new film by Christophe Barratier (who also directed The Chorus or Die Kinder des Monsieur Mathieu, also in French with German subtitles). The book, as well as the 1962 film version, happens shortly before World War I and the only girl is the gang is called Marie. In this newest version, it is the eve of World War II and the girl is Violette, aka Myriam of Jewish descent and she is hiding in the village away from Nazi discovery. This Jewish or political reference does not come up in the original book (which I read in German). Perhaps a book is world literature when it is relevant in any decade and can easily survive small changes and new interpretations, as this one does.

I was most impressed with the free lives of children in a small village: children with no money, no LEGO or computer games, no means of transportation or MacDonald’s. They made “weapons” from sticks and collected stones for their sling shots (which they used expertly), much like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. They ran and jumped and, most of all, expertly climbed trees to hide or to pose as lookouts. Take a look around your neighborhood: are there any children sitting in nearby trees right now? Definitely none in my metropolitan Hamburg street and it’s a school holiday. It was heartening to see laundry hanging outside on clotheslines and flapping in the breeze – another disappearing cultural characteristic. How many young people know the word for “clothes pen”?

I wonder if adults will enjoy the film more than children. Perhaps children will be interested in the lives of other children 75 years ago. There is certainly enough action and excitement, and the acting is fine. The history of its origins alone makes the film worth your time and interest.