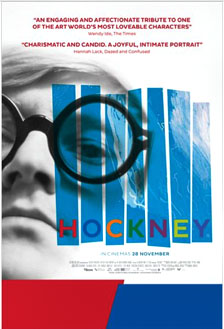

UK | USA 2014

Opening October 15, 2015

Directed by: Randall Wright

Writing credits: Documentary

Principle actors: David Hockney, Arthur Lambert, Colin Self, Celia Birtwell, John Kasmin This is what a documentary should accomplish! Keep the audience engaged, even entertained, and entice them to research the subject further. Rarely have I enjoyed a documentary about an artist more than this one on the multitalented British painter David Hockney (*1937) who became first known in the early ‘60s as a representative of English Pop Art. Since then his art has evolved continuously, frequently implementing up-to-date technologies. It has to be a win-win situation for a filmmaker to have a subject like Hockney: he is animated, witty, unconventional and stylish, and likes to share anecdotes and thoughts on his (and other’s) art. In 1961 he moved from his native Yorkshire to New York City, before making Southern California his adopted home. It represented to him the energy of the United States and the flair of the Mediterranean, and remained a great inspiration to him. The film—accompanied by a fantastic original score by John Harle (a rare perfect fusion with the visual)—is a collage of recent interviews as well as some from earlier decades. There are conversations with friends, family and gallerists. I wished they had been identified not only with their names but also in what capacity they know the artist. Vintage footage with the artist and recent interviews alternate back and forth and are not dated. I would have liked that additional information but admit, it somehow has the effect of showing the artist then and now are still the same, as unconventional and full of spunk as ever. (

This is what a documentary should accomplish! Keep the audience engaged, even entertained, and entice them to research the subject further. Rarely have I enjoyed a documentary about an artist more than this one on the multitalented British painter David Hockney (*1937) who became first known in the early ‘60s as a representative of English Pop Art. Since then his art has evolved continuously, frequently implementing up-to-date technologies. It has to be a win-win situation for a filmmaker to have a subject like Hockney: he is animated, witty, unconventional and stylish, and likes to share anecdotes and thoughts on his (and other’s) art. In 1961 he moved from his native Yorkshire to New York City, before making Southern California his adopted home. It represented to him the energy of the United States and the flair of the Mediterranean, and remained a great inspiration to him. The film—accompanied by a fantastic original score by John Harle (a rare perfect fusion with the visual)—is a collage of recent interviews as well as some from earlier decades. There are conversations with friends, family and gallerists. I wished they had been identified not only with their names but also in what capacity they know the artist. Vintage footage with the artist and recent interviews alternate back and forth and are not dated. I would have liked that additional information but admit, it somehow has the effect of showing the artist then and now are still the same, as unconventional and full of spunk as ever. (

Hockney is a broad-stroke film about a contemporary, significant British painter covering pertinent phases: childhood, art school, love affairs, and living in London, and USA. Born in 1937, the world’s strife barely touched David Hockney, “Life is always interesting for children, or at least it should be”. Quote (Hockney’s) cards separate segments. New York was David’s go-to party city, and Los Angeles “a good place to hide”. Generous amounts of archival footage—much from Hockney— insert actualities; friends add antidotes, e.g. what made David color his hair blonde, Santa Monica surfers’ influence. Director Randall Wright’s faux pas is retaining copious extraneous information that neither adds to or moves the narrative forward. Understandably, at 113 minutes, redundancy is unavoidable.

The most absorbing aspect of Hockney is Hockney: David tells us his reasons for certain artistic choices as we view his work and its evolvement, about Peter – “I think the absence of love is fear”, his photography – “I’m just a snapper, really”, and how he always looks for new tools. He wants people to think differently, to view (nature) differently: “… wider perspectives are needed now”, and “You can always go back to nature for things”. Disappointingly, we do not hear from or see enough of Hockney.

The excitement, depth, and range of the painter’s work – watch for a glimpse of the 9-camera car at the end – is not conveyed. Paul Binns’ editing is confusing; there are numerous interviewees—I stopped counting at ten—but without sufficient lower-third caption cards, Binns and Wright assume audiences know who and what they are. Why more screen time is not allocated to Hockney is the conundrum. David Hockney’s approach to life is astute, unapologetic: “I lived in Bohemia and Bohemia is quite a tolerant place”.