1/2

1/2 Chile | France | USA 2016

Opening January 26, 2017

Directed by: Pablo Larraín

Writing credits: Noah Oppenheim

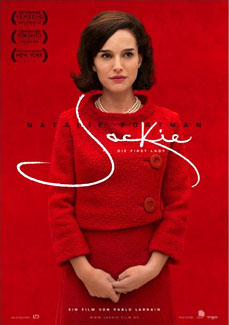

Principal actors: Natalie Portman, Peter Sarsgaard, Greta Gerwig, Billy Crudup, Billy Crudup, John Hurt, Richard E. Grant

The film Jackie took some days to seep into my bones. I did not have an immediate reaction to the film; the after-talk in the foyer of the vintage theater rendering me incapacitated to giving a quick review. Many films have been made of both John and Jacqueline Kennedy. I remember being in my LA apartment, stunned at Oliver Stone's version, replaying the archival footage of the assassination. But I have not seen a film about a widow’s immediate grief, a mother asking a friend how she will tell her children about their father's death.

The film Jackie took some days to seep into my bones. I did not have an immediate reaction to the film; the after-talk in the foyer of the vintage theater rendering me incapacitated to giving a quick review. Many films have been made of both John and Jacqueline Kennedy. I remember being in my LA apartment, stunned at Oliver Stone's version, replaying the archival footage of the assassination. But I have not seen a film about a widow’s immediate grief, a mother asking a friend how she will tell her children about their father's death. A week later, Jackie was still in my thoughts. And not for the breathtaking costumes that were an exact likeness or the physical unlikeness of Peter Sarsgaard's Bobby Kennedy. It was the intense portrayal of Jackie played by the unrivaled Natalie Portman and her surreal life during the four days of losing a private partner and a country's leader. It was human, raw, and real to even those who were not around this time period. Wonderfully casted, the film builds its footing around the interview between Jackie and journalist Theodore H. White, played convincingly by Billy Crudup, while jumping back into the recent and not so recent past.

Four days in public history, four days of private misery, the film Jackie shows a snapshot of grief, of the ability of the human heart to cope and transcend, and the aptitude of superb movie making at its finest: to make us think and feel and linger long after the credits have rolled. ()

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while riding in a limousine as his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, sat next to him. Jackie was only 34 years old when she was transformed from First Lady of the United States into a widowed mother of two small children and a symbol of American bereavement. Pablo Larraín’s remarkable film is set in the days immediately following the assassination, as Jackie (Portman) plans her husband’s funeral and prepares for life after the White House.

Despite being in shock, Jackie remains dignified in public. Yet Portman skillfully captures the ever-shifting balance of despair, turmoil, doubt, and decisiveness that Jackie shows to confidants in her innermost circle, including Bobby Kennedy (Sarsgaard) and Jackie’s childhood friend and White House Social Secretary, Nancy Tuckerman (Gerwig). These private conversations, many in flash-back, form the basis of Noah Oppenheim’s excellent screenplay. But it is two confessional – or seemingly confessional – conversations that Jackie has with two different men, a journalist and a priest, that constitute the film’s backbone and expose Jackie’s keen understanding of her power to definitively shape the legacy of the Kennedy White House years. Portman is magnificent as Jackie, and her embodiment of such an iconic figure is extraordinary.

The journalist (Crudup), although never given a name in the movie, is based on Theodore White, who interviewed Jackie for a feature in Life magazine in those grief-stricken November days. Oppenheim’s script draws on White’s extensive notes, and uses this exchange to show off how aware Jackie is of the power of public relations and of making the right visual impact, especially using the relatively new medium of television. The movie draws insightful parallels between Jackie’s careful restoration of the White House – made famous through her 1962 televised tour of the renovations – and her understanding of the importance of getting the visual, even theatrical, aspects of Kennedy’s state funeral exactly right.

Portman’s Jackie, well aware of the fate of previous widowed-in-office First Ladies, knows how to put on a composed public face despite overwhelming grief. (Having lost two of her children in infancy, Jackie has had practice.) One of the most striking elements of this movie is how Larraín uses the unsettling score, by the young composer Mica Levi, to represent Jackie’s anguish. A jarring arrangement of warped strings sounds like her jagged nerves, which she tries to soothe with booze and pills. Rarely has dissonance sounded so perfectly appropriate. This elegiac, dreamlike movie is so successful, and so addictively watchable, because Larraín and Portman portray one of the twentieth century’s most famous women in an entirely new light, in an homage to strength under duress.

You just can’t look away from close-up after close-up of Natalie Portman slowly morphing into Jacqueline Kennedy on screen. Blatant voyeurism and reverential fascination become entangled as you are swept back to November 22, 1963. Memories and emotions you have long buried someplace very deep swirl back to haunt you. Mica Levi’s hauntingly dirgeful score pierces your very heart. (You may listen to it at http://www.foxsearchlight.com/fyc/film/jackie/soundtrack/.)

Jacqueline Kennedy was the female icon to my generation as Jack Kennedy (Caspar Philipson) was the political idol. It is not only Jackie’s breathy voice that Portman so perfectly captures. She is Jackie dignified and suffering; she is also Jackie’s calculated performance persona, dignified and suffering. Jackie is a film which puts the First Lady at the center of the universe with the men occupying space as mere tangential figures.