1/2 |

1/2 |

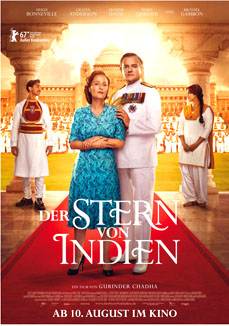

UK | India 2017

Opening August 10, 2017

Directed by: Gurinder Chadha

Writing credits: Paul Mayeda Berges, Moira Buffini, Gurinder Chadha

Principal actors: Gillian Anderson, Hugh Bonneville, Michael Gambon, Manish Dayal, Huma Qureshi, Lily Travers, Simon Callow  “History is written by the victors.” After three centuries ruling India, in 1945 the last Viceroy arrives with family (Anderson, Travers) in tow. Lord Mountbatten’s (Bonneville) mission: to oversee returning India to the Indians. “The sooner the better,” Pugs (Gambon), and existing staff point out. The friction is volatile among Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims and the respective political parties; instead of a united India, the Muslim leader Ali Jinnah (Denzil Smith) insists on a separate country, Pakistan.

“History is written by the victors.” After three centuries ruling India, in 1945 the last Viceroy arrives with family (Anderson, Travers) in tow. Lord Mountbatten’s (Bonneville) mission: to oversee returning India to the Indians. “The sooner the better,” Pugs (Gambon), and existing staff point out. The friction is volatile among Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims and the respective political parties; instead of a united India, the Muslim leader Ali Jinnah (Denzil Smith) insists on a separate country, Pakistan.

Parallel action involves Aalia (Qureshi) and Jeet’s (Dayal) reunion and their attraction deepening as tensions mount among the residence’s domestic staff. Mountbatten’s solution is to change the date from June 1948 to August 1947. Given the unenviable task of drawing up new country boundaries is Sir Cyril Radcliffe (Callow). In record time the deed is done, albeit the independence celebrations ring hollow. “There’s nothing to celebrate,” says Mahatma Gandhi (Neeraj Kabi) as fireworks fill the sky.

Although this period is dense with facts about the existing conflicting interests, director Gurinder Chadha, who has a personal investment in the storyline, chose a three-prong approach for the film: maintain interest, make it well, and keep it entertaining. Shooting on location, Ben Smithard’s camera embraces the sumptuous, vibrant visual tapestry, adorned with Keith Madden’s costumes whether in the Viceroy’s residence or along India’s streets. Valerio Bonelli and Victoria Boydell’s editing, accompanied by A.R. Rahman’s music, bring all the pieces and factions together. The cast performs well: physically, the central characters eerily resemble Lord and Lady Mountbatten.

Is it historically accurate? More or less considering a massive amount of history is condensed to 106 minutes. The script and directing go light on the harsh, traumatic facts. But then, if Viceroy's House was not enjoyable it might not be digestible. Undoubtedly, films will follow that vigorously focus on historical components with more dramatic fervor. ()

Whatever will audiences in India and Pakistan make of this movie? As it begins we are informed that, “History is written by the victors” and as it ends we read that one of its leading characters has had an advisory role in its making. We are watching historical events from the British point of view.

Viceroy’s House is an epic movie on the scale of the eighties one about Ghandi, with which it is sure to be compared. This spectacle of colour and sound gives one point of view of events which took place 70 years ago. All the extravagance of the British Raj unfolds at the beginning of the movie when Lord Mountbatten of Burma, his wife and daughter, arrive at the viceroy’s palace, a building which is so big that it contains five hundred bedrooms. Mountbatten is the last viceroy of India and he is to end three hundred years of British rule while trying to ensure a peaceful changeover of power. Mountbatten is played by Hugh Bonneville (who has forgotten to shake off his Downton Abbey aura) and his wife Edwina by Gillian Anderson. Their ceremonial entrance to their new home provides a sense of the luxurious lifestyle which past viceroys have enjoyed.

At the same time but without any ceremony Jeet (Manish Dayal) joins the vast household staff and is to wait on the new viceroy. He soon spots Aalia (Huma Qureshi) a pretty Muslim servant in the palace whose father he had once befriended. Their subsequent love affair mirrors the country’s dilemma and watching them grapple with their problems adds a romantic angle to their country’s escalating agonies.

Viceroy’s House provides a lightweight approach and a one-sided account of historical facts and so the movie, in one sense, is a failure. It glamourises the British players and demonises and over simplifies the Indian and Pakistani ones. It is, however, enjoyable to watch if you are prepared to take it at face value rather than a balanced account of what really happened in 1947.