![]()

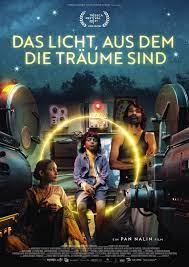

India | France | USA 2021

Opening May 12, 2022

Directed by: Pan Nalin

Writing credits: Pan Nalin

Principal actors: Bhavin Rabari, Bhavesh Shrimali, Richa Meena, Dipen Raval

The ode to celluloid storytelling by Indian writer-director Pan Nalin begins with his thanking filmmaking geniuses Eadweard Muybridge, the Lumiere Brothers, David Lean, Stanley Kubrick, and Andrei Tarkovsky before whisking audiences on a remarkably visual, captivating and celebratory journey. The Last Film Show’s protagonists provoke visceral feelings and raise excitement as Nalin spices things up with clips from Hindi films and Samay’s mother’s mouthwatering cooking—eat beforehand!

The ode to celluloid storytelling by Indian writer-director Pan Nalin begins with his thanking filmmaking geniuses Eadweard Muybridge, the Lumiere Brothers, David Lean, Stanley Kubrick, and Andrei Tarkovsky before whisking audiences on a remarkably visual, captivating and celebratory journey. The Last Film Show’s protagonists provoke visceral feelings and raise excitement as Nalin spices things up with clips from Hindi films and Samay’s mother’s mouthwatering cooking—eat beforehand!

Nine-year-old Samay’s (Bhavin Rabari, a charmer) consuming passion now is much to domineering Bapuji’s (Dipen Raval) chagrin. He insisted on taking his family to the dilapidated Indian Galaxy Cinema; awe-struck, Samay finds the projector riveting thus opening a window to untold wonders. Almost as if obsessed, Samay starts collecting colored glass he holds against light; serving tea from his father’s stand to passing rackety train’s passengers, nevertheless his friends join him in his enthusiasm. The mouthwatering school lunches gentle warmhearted Ba (Richa Meena) packs for her son turn into an open-ended ticket into the Galaxy. “Tastes like heaven,” mutters Fazal (Bhavesh Shrimali brilliantly balances dogged disenchantment with benevolence) munching Samay’s lunch; they strike a deal. The projectionist instructs Samay, as his booth becomes Samay’s temple of imaginative inspiration. His schoolteacher Mr. Dave (Alpesh Tank) proffers life-skill advice. Samay instructs his contingent of film aficionados, Manu (Rahul Koli), Nano (Vikas Bata), Badshah (Shoban Makwa), S.T. (Kishan Parmar), and Tiki (Vijay Mer); they make a projector and have screenings in an abandoned building. Then trouble comes twofold, shattering Samay’s dream and squeezing his family.

Semi-autobiographic and set in Pan Nalin’s native Gujarat, the film’s brilliance is in its crafting and thematic elegance. Text is minimal. Instead, Swapnil S. Sonawane’s extraordinary cinematography: the camera’s positioning and the impressive play of light, its evocative wide-angle backgrounds, extreme close-ups of nuanced faces to seasoning flakes sprinkled over steaming dishes, and spectacular details, e.g., Hindi cinema playing across Samay’s face. The editing (Shreyas Beltangdy, Pavan Bhat) is impeccable. The impish Rabari transforms every scene with his bewitching, huggable portrayals, and in relationship to Bapuji, Fazal, and teacher.

Nalin dwells on the positive not poverty, inserts a clanship repercussion for Bapuji, plus a parable-like allusion toward globalization ramifications, e.g., the scenes at the celluloid—shudder—graveyard. Equally, fertile innocence is laughingly embraced, e.g., the boys racing trains, eyeing lionesses, and bicycling merrily with celluloid-strip goggles. Nostalgia is fondled and creative inventiveness commemorated in the vibrantly rich Das Licht, aus dem die Träume sind. A must-see for every age, and you may want to see it again – it has that kind of effect. (See the original subtitled, if possible.) 110 minutes ()