![]()

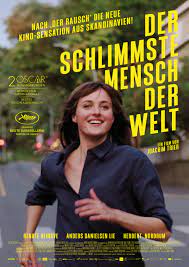

Norway | France | Sweden | Denmark 2021

Opening June 2, 2022

Directed by: Joachim Trier

Writing credits: Joachim Trier, Eskil Vogt

Principal actors: Renate Reinsve, Anders Danielsen Lie, Herbert Nordrum

Norwegian writer-director Joachim Trier’s newest film seems to appeal more to, oddly enough, men than women. The screenplay, co-written with Eskil Vogt, is structured with a prologue, a dozen chapters, and then an epilogue. The 121 minutes cover four years in Julia’s (Renate Reinsve) life as she approaches thirty; the first couple of years are dealt with expeditiously using quick cuts and a voice-over narrator (Ine Jansen).

Norwegian writer-director Joachim Trier’s newest film seems to appeal more to, oddly enough, men than women. The screenplay, co-written with Eskil Vogt, is structured with a prologue, a dozen chapters, and then an epilogue. The 121 minutes cover four years in Julia’s (Renate Reinsve) life as she approaches thirty; the first couple of years are dealt with expeditiously using quick cuts and a voice-over narrator (Ine Jansen).

Introduced in the prologue, Julia is a young woman trying on the many guises life has to offer, and jobs unencumbered by the shackles of maturity. Her fresh wholesomeness and spontaneity attract people to her, especially guys; she has affairs of the heart. By chance she meets Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), an underground comics writer, and they renew a relationship relaxing into their comfortable familiarity. Spending a weekend with friends of Aksel’s with children brings to the forefront the topic of having children; Julia is not ready, whereas he is. They celebrate special days with each other’s parents; Aksel prefers being with Julia’s unruffled mom Eva (Marianne Krogh) rather than her narcissistic father (Vidar Sandem). Not until Julia meets Eivind (Herbert Nordrum) does she acknowledge dissatisfaction with her current life. Out of Aksel’s flat and into Eivind’s life. Nevertheless, life still has some twists and boomerangs for Julia to experience before she qualifies for a fully-fledged classification.

Der schlimmste Mensch der Welt is neither a rom-com nor dramedy; the more accurate description is a sometimes amusing, somewhat sad look a Millennial’s life. Trier and Vogt’s protagonist is at best immature and at worst very self-centered, i.e., unlikable. Incongruently, the storyline tracks Julia over four years, yet turning thirty without a profession, or girlfriends, speaks volumes particularly about the film’s undercurrents. Perhaps the earlier two films of Trier’s supposed trilogy somehow made sense of what is missing here. Production values are solid: Kasper Tuxen’s cinematography, Olivier Bugge Coutté’s editing, and Ola Fløttum’s music. At least Reinsve, Lie, and Nordrum are engaging to watch. This easy to watch film is equally easy to forget. ()